Will the Euro Survive the Crisis?

Martin Feldstein asks whether the euro can weather the global financial crisis:

The current differences in the interest rates of euro-zone government bonds show that the financial markets regard a break-up as a real possibility. Ten-year government bonds in Greece and Ireland, for example, now pay nearly a full percentage point above the rate on comparable German bonds, and Italy’s rate is almost as high.

There have, of course, been many examples in history in which currency unions or single-currency states have broken up. Although there are technical and legal reasons why such a split would be harder for an EMU country, there seems little doubt that a country could withdraw if it really wanted to.

The most obvious reason that a country might choose to withdraw is to escape from the one-size-fits-all monetary policy imposed by the single currency. A country that finds its economy very depressed during the next few years, and fears that this will be chronic, might be tempted to leave the EMU in order to ease monetary conditions and devalue its currency. Although that may or may not be economically sensible, a country in a severe economic downturn might very well take such a policy decision.

Intrade puts the probability of an existing member leaving the eurozone before the end of 2010 at 27%.

posted on 11 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

How Not To Solve a Crisis

The Lion Rock Institute and International Policy Network have published a report by Bill Stacey and Julian Morris on How Not to Solve a Crisis. I agree with their assessment of the failure to bail out Lehman Brothers, which runs counter to the conventional wisdom:

The Lehman bankruptcy followed on 15 September, after talks with a few parties about a buyout failed. Early talks apparently failed because management held out for a higher price. Later talks failed because the government refused the guarantees sought by potential purchasers. The consequences of failure were large, with unsettled trades and frozen collateral disrupting markets everywhere. The Bear precedent had led many market participants to believe that Lehman would not be allowed to fail. Markets quickly priced the swing in policy, leaving all securities companies vulnerable.

The popular view among market participants is that Lehman should not have been allowed to fail. Yet if Bear had not earlier been rescued, Lehman would likely earlier have raised funds, counterparties would have more quickly protected themselves from risks and underlying problems would have been recognized sooner.

posted on 10 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

One Speech, Two Stories

The Australian:

RESERVE Bank governor Glenn Stevens last night flagged further interest rate cuts to help shore up the economy.

The AFR:

Reserve Bank Governor Glenn Stevens has signalled the bank’s unprecedented series of deep interest rate cuts may have come to an end.

Both papers fell victim to the view that every time the Governor speaks, he must be sending a signal on interest rates and if there is no explicit signal, then there must be an implied one. In fact, the RBA very rarely signals its policy intentions, not least because its view on the future direction of policy is not very strongly held. Unlike the rest of us, the RBA doesn’t need to anticipate its own actions, putting more value on policy flexibility than policy predictability.

posted on 10 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Did the Australian Economy Contract over the September Quarter?

The consensus forecast for September quarter GDP growth to be released on Wednesday is 0.2%, with growth through the year seen at 1.9%. Market forecasts range from -0.3% q/q to 0.5% q/q. Dusting off the old top-down GDP model, I also get 0.2% q/q.

Growth would then have to accelerate slightly to 0.3% in the December quarter to be consistent with the RBA’s year-end forecast of 1.5%. That may be a tall order given what is happening both domestically and globally, but by no means impossible.

The market is expecting a 75 bp reduction in the official cash rate to 4.5% tomorrow. With the RBA’s forecast for underlying inflation for the December quarter at 4.5%, the real cash rate will effectively be zero.

posted on 01 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Capital Xenophobia II

The Centre for Independent Studies has released my Policy Monograph Capital Xenophobia II: Foreign Direct Investment in Australia, Sovereign Wealth Funds and the Rise of State Capitalism.

The monograph revisits the subject of Wolfgang Kasper’s original 1984 Capital Xenophobia monograph. Wolfgang was kind enough to write the foreword to this update of his earlier work on the subject.

There is an op-ed version in today’s AFR for those who have access, reproduced below the fold for those who don’t (text may differ slightly from the edited AFR version).

continue reading

posted on 27 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Why Was Fed Policy ‘Too Easy’ Between 2002 and 2005?

Larry White has a new Cato Briefing Paper How Did We Get into This Financial Mess? White echoes a now widespread criticism of US monetary policy, that is was too easy in the first half of this decade:

The federal funds rate began 2001 at 6.25 percent and ended the year at 1.75 percent. It was reduced further in 2002 and 2003, inmid-2003 reaching a record low of 1 percent, where it stayed for a year. The real Fed funds rate was negative - meaning that nominal rates were lower than the contemporary rate of inflation - for two and a half years.

White also notes that the Fed funds rate was below that implied by the Taylor rule, a point that Taylor himself has also made.

That US monetary policy was easy at this time was no accident. It was a very deliberate policy choice on the part of the FOMC. Why was policy kept so easy for so long? One reason was the perceived threat of deflation, as Vince Reinhart recalls:

According to FOMC meeting transcripts from that year, then Chairman Alan Greenspan in November [2002] called deflation “a pretty scary prospect, and one that we certainly want to avoid.”

Then Gov. Ben Bernanke, now Fed chairman, said in September 2002, “the strategy of preemptive strikes should apply with at least as great a force to incipient deflation as it does to incipient inflation.”

In hindsight while there was clearly a strong disinflation trend back then, outright deflation didn’t appear to be as big a risk as the Fed thought. Annual growth in consumer prices never fell below 1% and was rarely below 2% after 2002.

The problem back then, Reinhart said, was “we didn’t know why inflation was going down as much as it was.”

That year, 2002, “was very much a story of uncertainty about the inflation process with some modest identifiable forces putting downward pressure” on prices, he said.

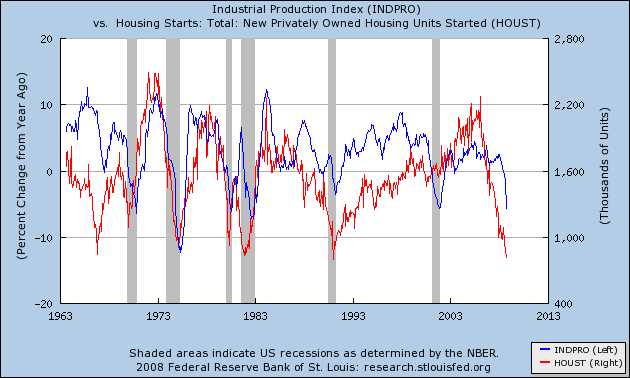

This puts the failure of US monetary policy to respond to the emerging US housing boom in its proper context. The following chart shows annual growth in US industrial production as a proxy for the broader economy, along with new privately-owned dwelling starts as a proxy for housing activity. Shaded bars are NBER-defined recessions.

The 2001 recession was exceptional compared to previous business cycles, in that housing activity did not see a significant downturn along the rest of the US economy. Industrial production was subdued coming out of the 2001 recession (note the double dip into negative growth), while housing continued to enjoy a strong expansion. If the 2001 recession could not tame the US housing boom, then it is hard to see how tighter US monetary policy could have done so without inflicting significant, and potentially deflationary, collateral damage on the rest of the economy.

One could argue that Fed policy was a success on its own terms, because it achieved exactly what it set out to do: pre-empt the threat of deflation.

posted on 21 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(35) Comments | Permalink | Main

Has the RBA Given the ‘Green Light’ to ‘Bubble’ Popping?

RBA Governor Glenn Stevens’ speech to CEDA last night has been widely interpreted as giving a ‘green light’ to deficit spending, as if politicians ever needed permission or encouragement from the Reserve Bank to ramp-up spending. The really significant part of Stevens’ speech went largely unnoticed:

in addition to the many useful steps being planned by regulators, perhaps we could pay more attention to the low-frequency swings in asset prices and leverage (even if that means less attempt to fine-tune short-period swings in the real economy); we could have a more conservative attitude to debt build-up; and we could exhibit a little more scepticism about the trade-off between risks and rewards in rapid financial innovation. This would constitute a useful mindset for us all to take from this episode.

The fudge word here, of course, is ‘more.’ More could simply mean giving greater weight to the implications of developments in asset prices for inflation and the overall economy. However, it could potentially extend much further, to an attempt by central bankers to actively manage asset prices at the expense, as Stevens suggests, of shorter-run demand management. As I argue here, the historical precedents for this are far from encouraging.

A more recent example of a central bank conditioning monetary policy on asset prices was the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s use of the trade-weighted exchange rate as part of a composite operating target between 1996 and 1999, known as the monetary conditions index. This practice was abandoned, because the well-known volatility of exchange rates and their very loose relationship with economic fundamentals made it a very poor basis for conducting monetary policy. The weaker the connection between asset prices and economic fundamentals, the stronger the argument against using asset prices as either targets or conditioning variables for monetary policy.

posted on 20 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(7) Comments | Permalink | Main

Regulating Ratings Agencies

The federal government is proposing to further regulate credit ratings agencies:

The Government also unveiled changes to the regulation of credit ratings agencies that will require them to hold an Australian Financial Services Licence and to report annually on the quality and integrity of their ratings processes.

The changes reflect a growing demand in the global investment community for greater oversight of ratings agencies, which have become the target of criticism, particularly for their role in rating structured finance.

This ignores the somewhat inconvenient truth that the role of ratings agencies in credit markets was itself mandated by regulation. As Charles Calomiris has argued, the regulatory power given to the ratings agencies encouraged them to compete on relaxing the cost of regulation to investors, generating huge fees for the ratings agencies in the process. Calomiris summed it up this way: ‘the regulatory use of ratings changed the constituency demanding a rating from free-market investors interested in a conservative opinion to regulated investors looking for an inflated one.’ Calomiris notes that both Congress and the SEC actually encouraged ratings inflation in relation to sub-prime CDOs, an unintended consequence of their promotion of rules designed to prevent ‘anti-competitive’ behaviour on the part of the dominant ratings agencies.

posted on 14 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

When Bubble Poppers Attack

I have an op-ed in today’s Australian, arguing against the view that central banks should explicitly target asset prices:

In 2002, prior to becoming Fed chairman, Bernanke gave a speech titled Asset “Bubbles” and Monetary Policy. Bernanke noted that “the correct interpretation of the 1920s is not the popular one: that the stock market got overvalued, crashed and caused a Great Depression. The true story is that monetary policy tried overzealously to stop the rise in stock prices. But the main effect of the tight monetary policy was to slow the economy. The slowing economy, together with rising interest rates, was in turn a major factor in precipitating the stock market crash”.

The singular cause of the Great Depression of the 1930s, in Bernanke’s view, was that the Federal Reserve fell under “the control of a coterie of bubble poppers”.

Bernanke was merely reaffirming a well-established consensus among economists, ranging all the way from John Maynard Keynes to Milton Friedman. In his A Treatise on Money, Keynes said: “I attribute the slump of 1930 primarily to the deterrent effects on investment of the long period of dear money which preceded the stock market collapse and only secondarily to the collapse itself.” Friedman’s 1963 A Monetary History of the United States also laid blame for the Great Depression squarely at the feet of the Fed and its attempt to become “an arbiter of security speculation or values”.

posted on 12 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(10) Comments | Permalink | Main

A Libertarian Defence of Alan Greenspan

The scapegoating of Alan Greenspan across the political spectrum has been shameful and shameless. It is therefore pleasing to see that the Cato Institute has published a timely defence of Greenspan by David Henderson and Jeff Rogers Hummel. Henderson and Hummel argue that:

Alan Greenspan stands out as the most competent—and arguably the only competent—helmsman of United States monetary policy since the creation of the Federal Reserve System…

his policy may have ended up slightly too discretionary. But that possibility hardly justifies the “asset bubble” hubris of those economic prognosticators who, only well after the fact, declaim with absolutely certainty and scant attention to the monetary measures, how the Fed could have pricked or prevented such bubbles…

Rather than demonstrating that monetarist rules are obsolete and free banking unnecessary, Greenspan’s policies suggest that the more thoroughly either of those two objectives is implemented, the greater the macroeconomic stability our economy will enjoy.

I made a similar argument here about how contemporary central banking closely approximates the free banking ideal of a market-determined monetary order.

posted on 10 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Education of Sallyanne Atkinson

ABC Learning Chair Sallyanne Atkinson learns political economy the hard way:

DEEP in debt, Sallyanne Atkinson appears stunned by the collapse of ABC Learning.

“I find that absolutely bizarre” the businesswoman who chaired the failed childcare corporation for seven years said yesterday when told 40 per cent of the centres are unprofitable.

“This is a business subsidised by the Government. How can it be unprofitable?”

posted on 09 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Self-Importance and the G20

Former Australian Treasurer Peter Costello once told us that the G20 was ‘important in itself,’ an idea to which he could easily relate. Former IMF Chief Economist Simon Johnson continues this fine tradition of explaining the relevance of the G20:

the fact that G20 heads of government will now start meeting (dinner is on November 14; mark your calendars) is most significant. Almost always, once a group like this meets, it can agree on its own importance and the need for another meeting.

I’m sure we can all sleep a little easier at night, knowing the G20 is on the job.

posted on 09 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

US Presidential Vote Equation

Ray Fair’s final US Presidential election equation update:

The final economic values (‘final’ as of October 30, 2008) are 0.22 for GROWTH, 2.88 for INFLATION, and 3 for GOODNEWS. Given these values, the predicted Republican vote share (of the two-party vote) is 48.09 percent. So the prediction is 51.91 for the Democrats and 48.09 for the Republicans, for a spread of 3.82.

The current situation is unusual in that the economy since the end of the third quarter appears to have gotten much worse. People may perceive the economy to be worse than the economic values through the third quarter indicate, which, other things being equal, suggests that the vote equation may overpredict the Republican share. But for what it is worth, the final vote prediction is 48.09 percent of the two-party vote for the Republicans. The Republican share of the two-party House vote is predicted to be 44.24 percent.

posted on 01 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Long-Run Wealth Accumulation and Household Debt

RBA Deputy Governor Ric Battellino tells the public what Steve Keen won’t:

Australian households have much bigger holdings of financial assets than financial liabilities. Financial assets at 30 June averaged around $275 000 per household while liabilities averaged $150 000 per household. Since then, we estimate that average assets have fallen to around $245 000 per household, though this is still quite a strong position.

This balance sheet structure is very favourable in terms of maximising long-run accumulation of wealth, because the return on these assets over long terms exceeds the cost of debt by a substantial margin. The returns do not, however, accumulate evenly from year to year. Some years produce very strong returns while others produce negative returns.

posted on 30 October 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(4) Comments | Permalink | Main

Rudd and Greed

I have an op-ed in today’s Australian responding to the Prime Minister’s attacks on ‘the culture of greed’:

Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume noted as long ago as 1741: “Avarice, or the desire of gain, is a universal passion which operates at all times, in all places and upon all persons.” One cannot explain episodic phenomena such as financial crises with reference to a constant such as human nature or rationality.

The principal mistake the critics of free markets make is to assume that self-interest, greed and irrationality affect only private sector decision-makers. Politicians and regulators are just as prone to self-interested behaviour and do not become saints by virtue of elected or unelected office. The public sector and regulators are populated by the same species that is found in the private sector and financial markets. We should always be suspicious of claims to superior moral virtue coming from politicians.

posted on 29 October 2008 by skirchner in Culture & Society, Economics, Financial Markets

(4) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 22 of 45 pages ‹ First < 20 21 22 23 24 > Last ›

|